No Reasonable Person

Who gets to decide what reasonable means?

We live in a world of algorithmic echo chambers, where the media cherry-picks the most inflammatory version of every story, and your neighbour’s idea of common sense might be unrecognizable to you. We’re told society is more polarized than ever.

If that’s true, if we can’t agree on basic facts, let alone basic norms, then what happens to the legal standard that governs most of everyday life?

The reasonable person is the load-bearing wall of huge swaths of law including negligence, contracts, consent, and consumer protection. It determines whether you drove carelessly, whether that ad was misleading, or whether someone truly agreed to the terms in a 30 page contract.

It is the legal system’s version of common sense. The standard’s logic boils down to: we know it when we see it. As the consensus of the community fragments, do we even know what reasonable means anymore?

The Shrinking Ground

The definition of a reasonable person has never been static. Over the last few decades, the law has consistently demanded more diligence from the average person while technology has made it increasingly impossible to provide it.

In the 1990s, the reasonable person was a reader. If you bought software, opened the box, and kept it, you agreed to the terms inside. The court assumed you could have read them and returned it if you disagreed. By the 2000s, the internet shattered that assumption. In 2002, the court recognized that online information could be technically available yet practically invisible, ruling that terms buried in websites were not binding.

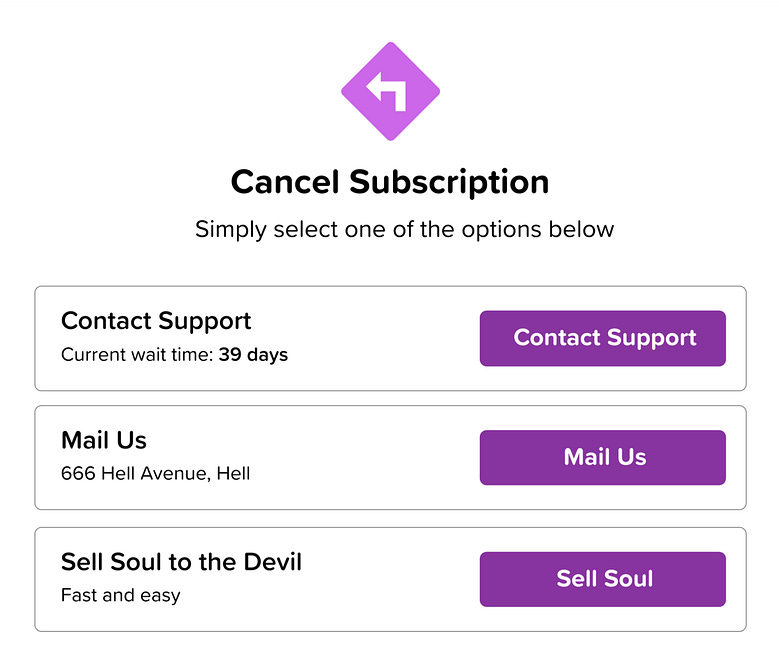

By the 2010s, dark patterns emerged, engineered to exploit human attention. These were manipulative user interfaces that tricked users into doing things they did not intend to do, such as signing up for subscriptions. Dark patterns were designed to hack the reasonable person’s brain.

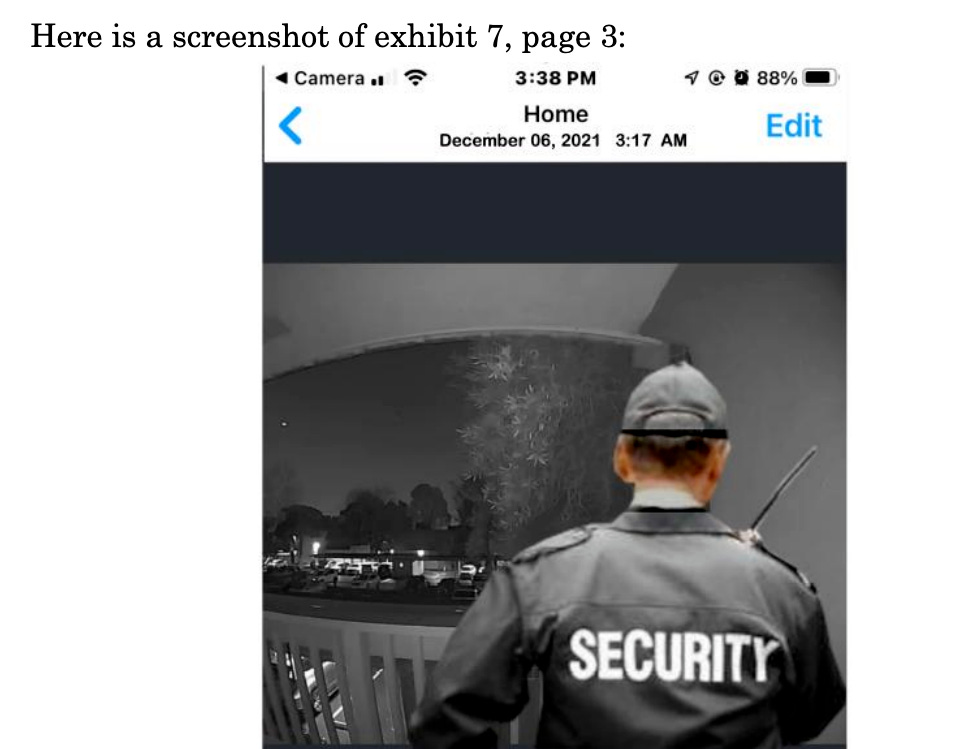

Fast-forward to 2025, and we have reached a point where we can question what we’re seeing with our own eyes. In Mendones v. Cushman & Wakefield (2025), the judge dismissed a lawsuit because the plaintiffs submitted AI-generated deepfake video testimony as evidence. The judge spotted the fakes thanks to robotic speech, mismatched mouth movements, and a color figure stitched onto a black-and-white camera background.

States are responding and passing laws requiring reasonable diligence from attorneys to verify the accuracy of GenAI materials. Louisiana already passed a law requiring reasonable diligence from attorneys to verify evidence isn’t synthetic.

In three decades, we have transitioned from the reasonable person reads the label to the reasonable person cannot tell reality from AI-generated photos and videos.

Can AI Read the Room?

If humans no longer agree on a standard, can AI do it for us?

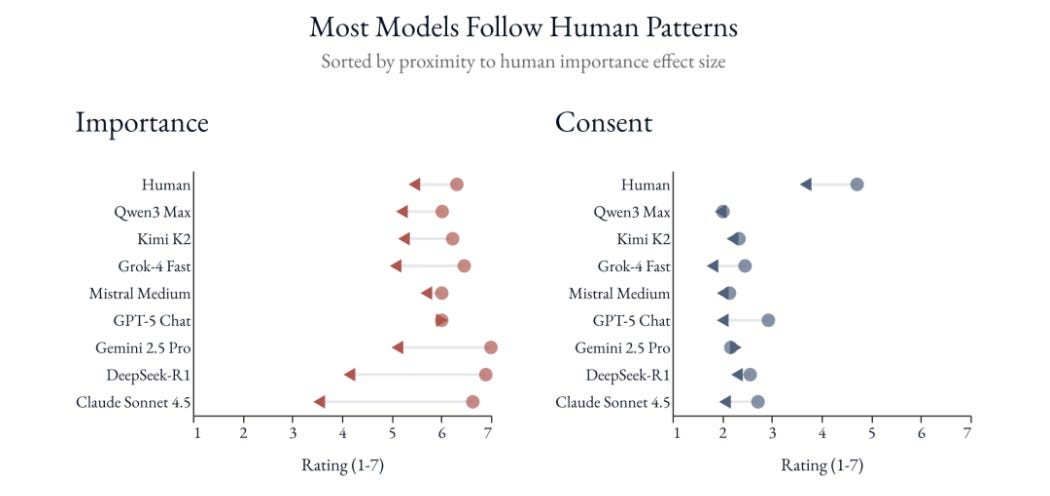

Yonathan Arbel, a law professor at the University of Alabama tested this in a recent study, The Generative Reasonable Person. He ran over 10,000 simulated judgments to see if AI could read the room of human intuition.

The results suggest that AI is better at replicating our messy, non-logical quirks than we expected. In negligence tests, the AI ignored the textbook cost-benefit analysis. Instead, it prioritized social norms, judging individuals harshly for skipping common safety precautions even if they were expensive, just as real people do.

The study also found that AI mirrored the contract formalism of laypeople. While lawyers might dismiss fine-print fees as negotiable or legally dubious, the AI (and the average person) perceives these charges as more binding and fairer. AI absorbed the community's gut feeling.

The Emperor Has Fewer Clothes Than We Thought

The most interesting finding comes from research on consent. Imagine someone buying an item to earn reward points for a trip. They plan to donate the item anyway. In one scenario, the clerk lies about the product being a bicycle when it is actually a camera. In another, the clerk lies about whether the purchase earns reward points. Logically, the reward points matter more to this buyer. That's the reason for the purchase. But humans consistently say the buyer consented more in the reward points scenario than the wrong-product scenario, even though the reward points deception is the one that actually harms them.

It makes no logical sense, yet AI replicates this counterintuitive pattern perfectly. So did we ever understand reasonableness ourselves? Maybe it was never a principle we could explain. Maybe it was always just a pattern we followed, and the legal system dressed it up in doctrinal language after the fact. If that’s true, AI isn’t just a new tool for measuring reasonableness. It’s a mirror showing us that the emperor of legal reasoning might have fewer clothes than we thought.

Democratizing the luxury of reasonableness

For too long, lawyers have been accessible only to those who have the time and/or money to fight for their rights. If a landlord refuses to return a deposit over normal wear and tear, the average tenant lacks the resources to prove their view is the reasonable one.

AI could level this playing field through by running hundreds of simulated judgments for various types of disputes, costing almost nothing compared to a human focus group. It’s not a replacement for a real jury. But it’s infinitely better than nothing, which is what most people currently have.

And there are numerous applications. It could give consumers empirical data points to defend their claims, offer judges a gut check to see if their professional intuition aligns with a broader demographic sample, and allow companies to stress-test whether their products or services are likely to mislead a simulated panel of consumers before going to market. If generative reasonable people can provide even a rough approximation of community judgment, they redistribute a form of legal power that currently flows almost exclusively to those who can pay for it.

The Feedback Loop

Despite the promise, there are catches. AI suffers from majority bias and frozen norms. LLMs gravitate toward majority views by design, rather than a random sample, potentially flattening minority perspectives and encoding the biases of the majority into the standard.

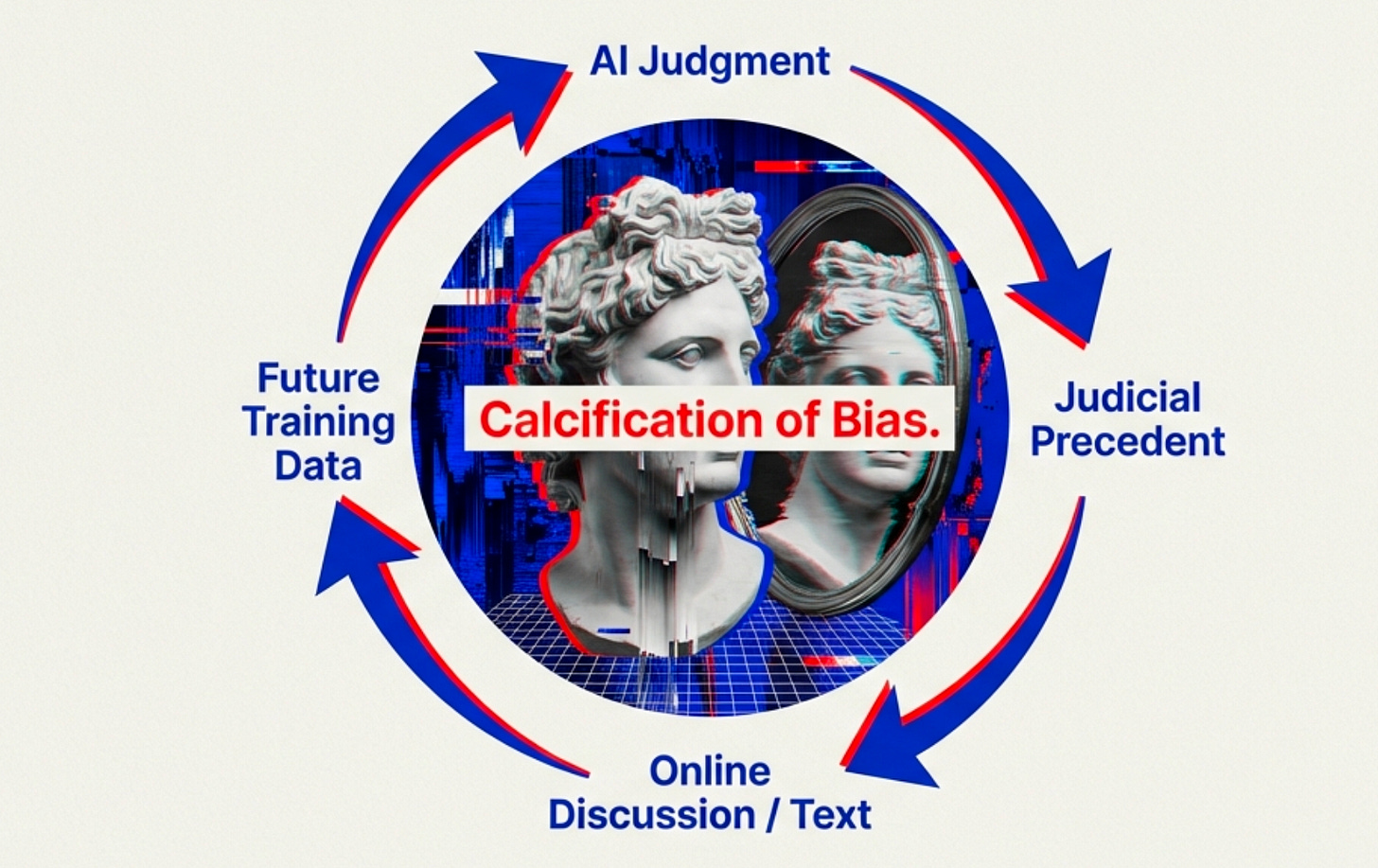

Then there is the feedback loop. If generative reasonable people start informing judicial decisions, those decisions become precedent. Precedent gets written about, analyzed, discussed online and eventually feeds future AI training data. The model’s output shapes the norms that shape the model’s next output. A closed loop. Today’s AI-informed ruling becomes tomorrow’s AI training signal. We’ve seen this in other domains: recommendation algorithms that narrow taste, content feeds that amplify engagement over accuracy. The legal system should learn from those cautionary tales before embedding the same dynamic into judicial reasoning.

Forcing a More Honest Argument

On one hand, we desperately need better tools for surfacing what people actually think because judges’ intuitions, jury selection, and expensive surveys aren’t cutting it. On the other hand, we’re asking AI to model a reasonable consensus at the exact historical moment when consensus feels like a fiction.

The generative reasonable person is not a replacement for human judgment, but it is a necessary challenge to it. By using AI as a gut check rather than the final word, we can finally begin to examine the standards that govern our lives and perhaps admit that they were never as reasonable as we claimed.

Professor Arbel’s conclusion hit home:

“The reasonable person standard has always promised democratic legitimacy: law speaking in the voice of those it governs. But what ordinary people think, how they experience the world, and what they mean by their words, has always been illegible to the state. Generative reasonable people help make real ordinary people visible.”

A flawed empirical tool is better than no empirical tool at all.

Yonathan A. Arbel, “The Generative Reasonable Person” (2025). Available on arXiv and SSRN.